Taking Wellesley by stormwater

The Wellesley Department of Public Works is doing the rounds at town boards and committees, feeling them out for what could become a new stormwater utility that yes, would result in another bill.

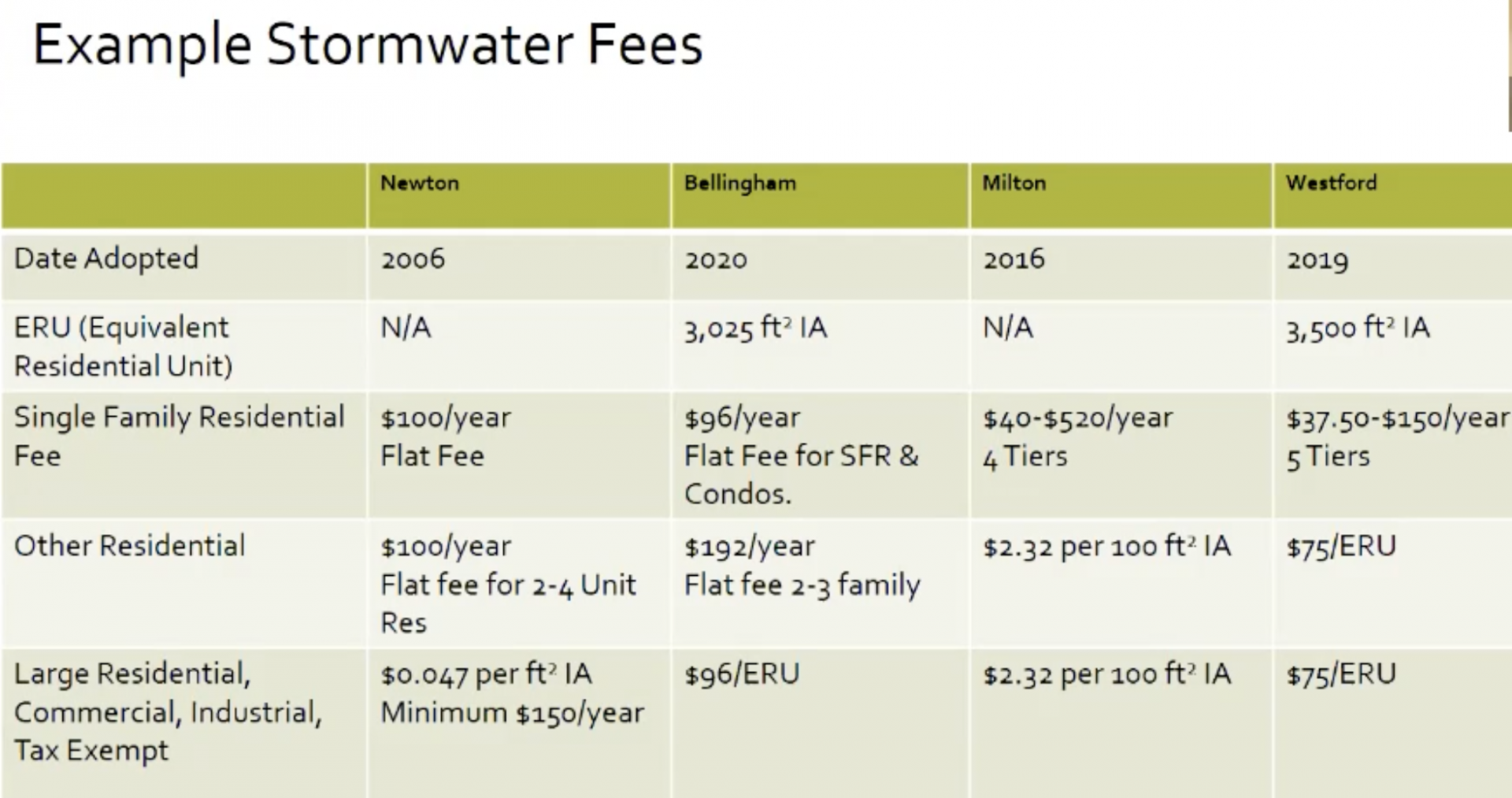

While no one wants to hear about another thing that’s going to make Wellesley an even more expensive place to live in light of ever-rising taxes and soon-to-be soaring water rates, the reality is that stormwater treatment and management needs to be paid for one way or another. The cost currently comes out of the town’s general tax fund, but the DPW is exploring whether a fee-based utility service, like for water and sewer, might be a more stable and fair way to cover skyrocketing stormwater-related costs in the face of tougher standards from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that will require more street sweeping, better cleaning of the town’s 4,500 catch basins, increased maintenance of Wellesley’s nearly 30 water interconnection points, etc. (we could be talking an annual $200 bill, on average, depending on the imperviousness of your property).

“The targets that Wellesley is being required to meet are going to require a great deal of expenditure in the coming years,” DPW Director David Cohen told Advisory at its Dec. 8 meeting. “We can continue to do that through our general fund, but what happens with the general fund is that you risk the peaks and valleys depending on the financial picture at the time. So the EPA is really encouraging communities to establish utilities… enterprise funds… to ensure that the revenues are there to clean up the water.”

The DPW, which has partnered with a consulting firm, has shared its presentation and fielded questions before the Board of Public Works (near the start of the Nov. 9 meeting), Advisory Committee, Planning Board (Dec. 9 meeting, near start of Wellesley Media recording), and Select Board (20 minutes into Wellesley Media recording). Presentations before the Natural Resources Commission and Climate Action Committee are to come, as are meetings with large property owners. The aim is to determine whether “this is the right idea at the right time,” Cohen told Advisory.

Other options raised along the way include addressing the issue of stormwater management costs via a more general stabilization fund.

Whether the DPW has something to present before Annual Town Meeting remains to be seen. A timeline shown to Advisory shows that if a utility was to be in effect for FY23, you could be seeing a bill before year end. Another option would be to just take the money out of the general fund for the first year and then figure out the billing, fee, and abatement structure for the following year. Grants are a possibility for covering costs, but they are hard to come by.

Wellesley would be a relatively early adopter of the utility model for stormwater management in Massachusetts, which currently counts just over 20 such communities, including Bellingham, Newton, and Westford. Across the country, though, some 1,800 municipalities have gone the utility route, as of 2020.

Take your pick of DPW briefings on the subject via Wellesley Media recordings (Public Works, Planning, Select Board).

I’ll go with the Dec. 8 Advisory Committee meeting, where the briefing was shorter than the others. I have watched the Board of Public Works and Select Board briefings too, where participants have asked good and basic questions, like what the heck is stormwater anyway? You definitely can use a glossary of terms when coming up to speed on stormwater management, as even words like “stormwater” (more than just rain…) and “watershed” that you’ve probably heard of might not mean exactly what you think they do.

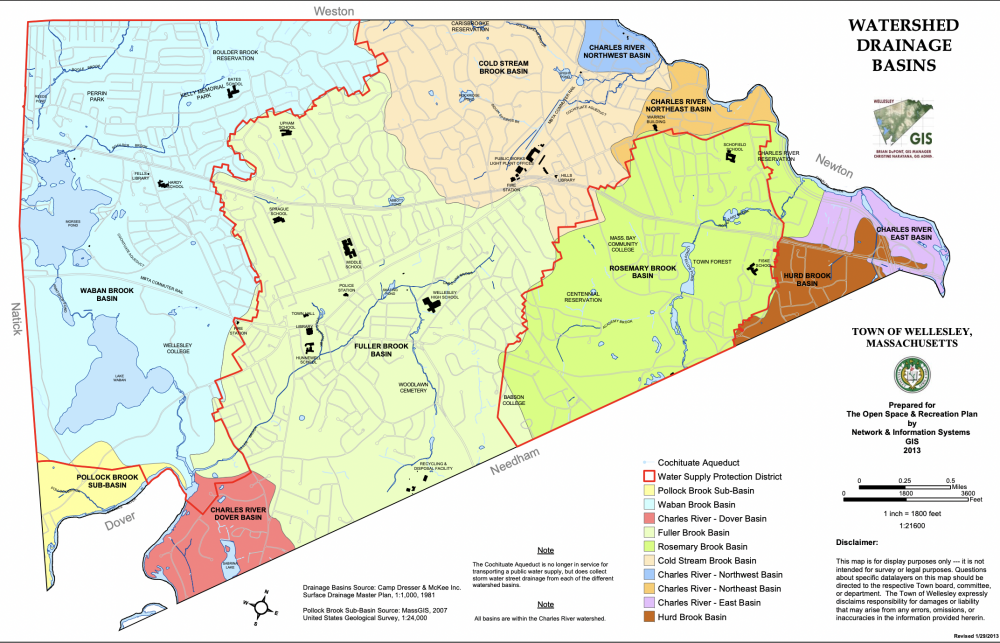

The DPW describes its efforts to comply with its EPA’s MS4 (municipal separate storm sewer systems) permit as possibly requiring establishment of a utility (via what’s referred to as an “enterprise fund”) to handle operations, management, and capital costs associated with making sure the water Wellesley discharges into the Charles River is clean, and in particular, free of phosphorous that stems from fertilizers, pet waste, road salt, and more.

Among the DPW’s challenges in establishing such a utility would be coming up with a fair system to charge residential and commercial property owners based on the imperviousness of their property (i.e., contributions to water pollution) and whether they do any stormwater treatment themselves. Overall, more than a quarter of Wellesley is considered impervious. The DPW’s goal, if a stormwater utility flies in town, would be to come up with a fee structure that’s easy for the town the manage for property owners to understand. Incentives would most likely be aimed at larger property owners, where investments designed to address stormwater management would clearly pay off.

What’s clear from the DPW presentations is that stormwater management is getting more complex and expensive, and the ramifications of climate change and flooding aren’t yet clear. The town has already taken many steps to address environmental concerns of stormwater, including the management of projects such as the Fuller Brook restoration and more recently, the softball field projects. Going forward, public-private partnerships will be key, too, as new developments take shape in town.

Town Engineer Dave Hickey told the Planning Board on Dec. 9 that “Our past practices might be good, but they’re not the end-all, be all for the MS4 permit… they won’t satisfy all the regulatory requirements.” The DPW is going to have to do things more frequently and at larger scales, and that’s going to cost more money.